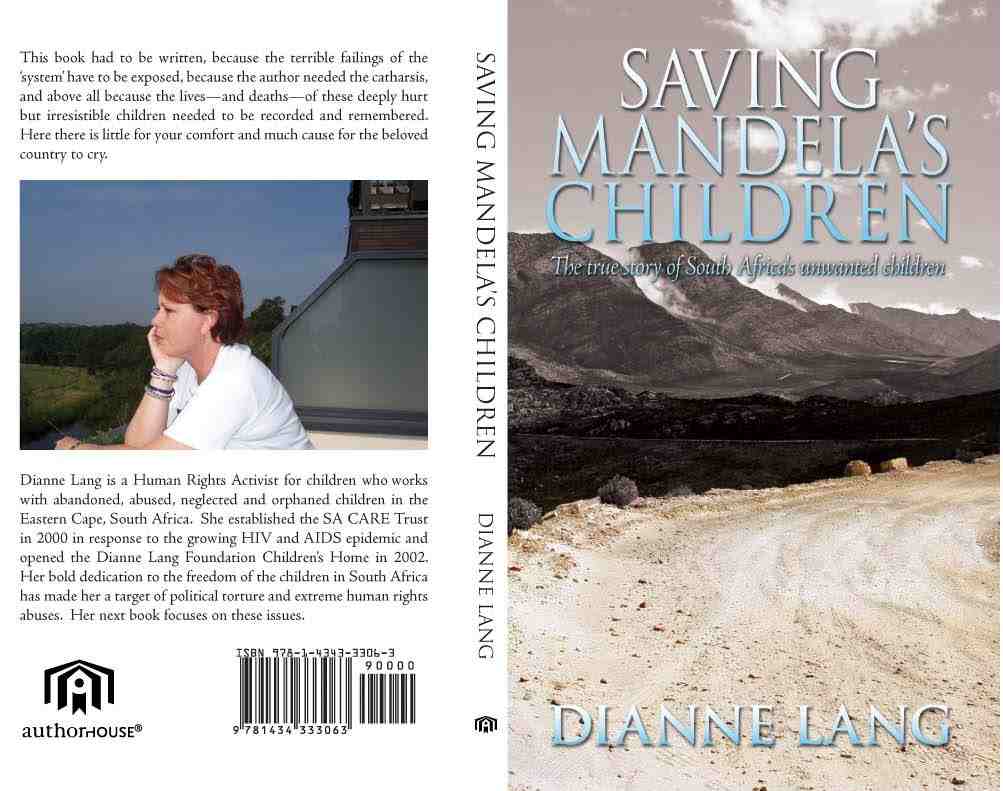

Sample chapter from...Saving Mandela's Children...by Dianne Lang

|

Dedicated to Amore Morgan |

I woke up with a jerk. Someone was yelling.

“Mama D. Mama D. Luke is getting bad. Come quickly”.

I jumped out of bed and ran down the passage. Luke was ashen, lying with his big eyes looking at Amore as she held him. Amore was one of the many young people that I had gathered around me during my life. I always seemed to have with me a young person who was troubled. She had come with me to Middelburg because she had problems with her family, and although she did not take Patience’s place, she did have a very special place in my heart.

Luke had the most beautiful eyelashes and eyes I have ever seen on any child. Luke was eighteen months old and dying of AIDS. He had been living with us for almost ten months. When his mother brought him to us to take care of, the doctor told us that he did not have long to live, and the best that we could do for him was to make him comfortable. But we never believed doctors. We lived as though there were no tomorrow. Luke had been sick before and we had managed to get him well again. He had even managed to go through the baby stages, getting teeth, sitting up, trying to stand and walk, all the things that he was not able to do when he arrived. For some reason, we just all believed that Luke would be like all the rest. He would just grow up and be like all the other kids. Whenever the children got too sick, they would be brought into my bedroom and there they would stay until they were well enough to join the others. When they got really ill, I would put their little bodies against my chest, wrap a baby blanket or towel around the two of us, and let the baby feel my heartbeat. I would not put them down other than to change their nappies or to feed them, and then back they would go, tied to my chest. And time and again, they would get better.

Now was the time for Luke to come to my bedroom. When Luke became ill this time, Amore asked me if she could take care of him.

I agreed, but I did warn her that it might be traumatic. Amore was only twenty at the time. She wanted to be with him 24 hours a day so that he would not be alone for one minute. I agreed, as I would be there as well.

Amore sat rigid in the chair, her eyes as wide as saucers. I could see she was afraid that Luke might be dying and she was scared of death. Luke was conscious but in pain. His frail little body was sore and as I gently took him from her arms, he moaned faintly. His breath was coming in short sharp intakes and the out breaths just left his chest without any effort on his part. His heart was racing. You could see how the artery was fluttering in his neck. He was looking past me as though he was seeing something there that we could not see. “He will not die now Amore, but Luke is dying”, I said gently. I knew that there was nothing more we could do for our little boy. He was beyond our help. This time we would not be able to save our boy. “Nooooo!!!”, she howled as she leaned over and put her head in her lap. Her body shook with grief and her anguish poured out of her in great big sobs. When Amore had calmed down a bit, I asked her, “Do you still want to be with Luke till the end?” “Yes”. “Then come”, I quietly encouraged her. I called the staff and told them that Luke did not have long to live and they went to break the news to the other children. The children were sad and crying, but they all came and said goodbye to Luke, some kissed him, others touched his forehead and others just stroked his little feet. The staff stood around and said a prayer. I called Father John and he came and baptized Luke and gave him the last rites. Father John called me aside and said, “Dianne, you are forever calling me out to baptize your children at all hours of the day and night. I think you should now do it yourself. I can’t always be coming out, day and night, whenever you think one of your children is going to die and then they don’t. All you have to do is say: “I baptize you in the Name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit”. OK?”. “Yes, Father, thank you for coming”, I said. We sent word out to try and find Luke’s mother, but she had gone to Cape Town

It took eighteen hours for Luke to die. He never lost consciousness. He was awake the whole time. He suffered for eighteen hours. His breathing became more and more erratic. He could not swallow. He could not pass urine. He could not cough. He would take a deep breath, exhale and then there would be no breath for a long time and then he would take another deep breath. And so it would go on. And on…and on...and on. Amore grew tired. I told her to go and have a sleep. I would wake her if there was any change. We were taking it in turns holding Luke in our arms, talking to him and singing to him all the time. Amore curled up on the couch with a blanket and was soon fast asleep. The emotions of the day were draining and she needed to rest. Who knew when this would end? In the stillness of the night, Luke’s breathing became more pronounced and his suffering became more evident. I longed for the suffering to end. This poor little mite was struggling to breathe for hour after hour. I had already phoned the pharmacist and asked her if there was anything that would ease his suffering and she had told me that there was nothing. I knew from experience that there was nothing at the hospital. What could I do to help this little soul? The minutes ticked by so slowly. I kept looking at the clock. How much longer does this have to go on? I started to pray. “Please God, stop this suffering. Take this child into your care now. This is enough. Don’t let this carry on any longer. Please don’t let him struggle for one more breath. Just let him stop breathing”. But no one heard. The silence was made more deafening by the incessant struggle for the next breath from Luke.

OK, I thought. I will do something now. Amore is asleep. No one will know what I am about to do. I will take a pillow and put it over his mouth and then he will stop breathing and it will be over. Not even God listens. To allow this to carry on is beyond cruel. I lean over and take the small pillow out of the pram. I hold it up in my right hand. Luke is lying in my left arm. He has stopped breathing. I don’t have to do it. Thank you, God. Then he struggles for the next breath. I have to do it. I hover with the pillow still in my hand. I hesitate, knowing that I have no right to take another’s life, but at the same time consumed by the need to stop the suffering. I

move the pillow closer to his head. Closer still: the pillow is now just above his face. And still I hesitate. Do I or don’t I? I need to stop his suffering. I have an irresistible need to stop this awful breathing that is filling my brain and my mind and my soul with anguish and suffering from hell. He looks at me. Those big eyes of his look at me. What is he trying to tell me? Help me? But how? The pillow goes down on his face. Gently. My hand holds the pillow gently on his face. I pull the pillow away from his face and fling it across the room. I can’t do it. I have failed him. “Oh, Luke, my darling, darling little Luke, I am so sorry, boy. I am so sorry I could not make you well. I did my best, but you must go now my love. Please go now. Don’t stay any longer”. “Amore”, I call, “wake up, and come and hold Luke”. She stretches and comes over. I put Luke into her arms. He is still struggling to breathe. I tell her to tell him it is OK for him to leave us now. She does. It is not long and she screams and throws Luke at me. I catch him in my arms. He has stopped breathing. He will never breathe again. Our baby is dead.

I phone the hospital and tell them that our baby is dead. “What must I do?”, I ask. “You must phone the police”, they tell me. “Because if someone dies at home, it could mean that it is a homicide”. I phone the police and tell them that our baby has died. Two police officers arrive within minutes. They call the mortuary van over the radio. The mortuary man arrives and takes Luke. He opens the back door of the mortuary van and wants to put our tiny little Luke into the back of the cavernous vehicle. “Please can’t you take him in the front with you”, I beg. “OK”, says the man, obviously seeing how distraught Amore and I are. Luke leaves and our family mourns: the staff, the children, Amore, me. For the rest of the night, I cradled Amore in my arms. Little did we know what the next day would bring.

I had never had to bury someone before so I was learning the steps as I was going along. There was much to organize to bury Luke. There was a coffin to buy, a plot to purchase, and a funeral to organize. Amore and I went off to the funeral parlor to discuss the

cost of a funeral and realized that we could not afford it at all. When I told them that we would bury Luke ourselves we were promptly told that we would not be allowed to do that because we would not be given a death certificate. “Thank you very much”, I said as we sailed out of the funeral parlor. By this stage, I did not trust anything anyone in Middelburg told me and this smelled like a racket to me. Was this a way to get poor people locked into expensive funerals? Where were our constitutional rights? Now I needed to go back to my books and back to the telephone to find out how to go about getting a death certificate without going through a funeral parlors.

After numerous telephone calls I discovered that the death certificate story that I had been given was a scam that all the funeral parlous were using to ensure that they got all the business. No wonder no one buried their own family. All I had to do was go to the police station and get a burial order. It was that simple. Next was the purchase of a coffin. We went to three funeral parlous to find the cheapest coffin. They were all out of our price range, although at that point, any coffin was out of our price range. We were struggling to keep food on the table and had not paid the school fees yet. The end of the month was coming up and staff salaries had to be paid. On top of that, it was only two months to Christmas. Eventually, I asked a funeral parlor if they did not have a damaged coffin or one lying around that could not be sold that we could repair. The lady obviously took pity on us and went out into the back yard to take a look. She came back with a little white coffin that was damaged and falling apart. It was dirty and weathered from lying outside, obviously exposed to the elements for a long time. “Perfect”, I said, “how much?” “What about R100?” The deal was made and we left with the coffin. Amore was still so afraid of death or anything connected to it that she would not even carry the coffin. With bravado, I picked it up and carried it across the street and put it into the 4 x 4. With a little bit of paint, nails and screws, the coffin looked much better. The children painted pictures on the coffin and it looked quite festive: a sarcophagus fit for a boy prince.

All the preparations for Luke’s funeral kept us busy and focused, and I had little time for grief. There was much consternation at the staff meeting as they were very unhappy about us having a funeral and not using a funeral parlor. “What will the community think of us? They will think we are poor and will look down on us. It is our culture to use funeral parlors. We must also provide food for everyone who attends the funeral and there will be lots who will come because they want to see what goes on in the Children’s Home. We must also have all the dishes outside so that after the service at the grave, everyone can wash their hands before coming inside”. These were the arguments that they were giving me. One of the many problems that have frustrated me over the years of working in the community has been the use of the word culture. Having grown up in the Transkei, I know the customs and culture of the Xhosa people. Using funeral parlors was definitely not part of the culture. My mind wandered back to a workshop that I had taught where I had used an example of the necessity of using a seat belt in a car. One of the delegates told me that he would not use a seat belt because it was not part of his culture. “And using a vehicle is not part of your culture either. You should be riding a horse”, I retorted. The delegates howled with laughter. I have found that many people use the word “culture” as an excuse for doing or not doing something. Culture is also often used as another word for racism. And the annoying thing is that those who use this word so indiscriminately are those who have never grown up in a tribal system, but have grown up in cities and in a western environment. What they knew about tribal culture was dangerous. It was time for a serious talk to the staff regarding more than just culture and funeral arrangements. I needed to impress on them once and for all the dire financial situation we were in. For some reason, they were under the impression that I was a never-ending source and supply of all things, because whenever we needed something, I always seemed to come up with what it was we needed, when we needed it. However, it was more due to providence and good fortune that we always seemed to just make it.

I brought out our bank statement and showed them that we had a total of R1800,19 in the bank. I showed them my private banking account with an overdraft of R50 000,00 which had been keeping us afloat. I showed them the total monthly expenses. Not all of them grasped the seriousness of the situation, but they took it that I was not a never-ending supply of money and that I did not have any money to spare. I also had to tell them that I had sold my own home in Port Elizabeth Transkei

After more discussions, it was decided to have a short service at the Catholic Church and then we would walk to the nearest cemetery where we would bury Luke. After that, we would come home and have lunch and then have a video afternoon for the rest of the children. Organizing the church service with Father John was just a phone call. Organizing the grave site was another matter altogether.

To purchase a burial plot, I had to go to the Municipal Health Department. Amore and Jackson came with me. Jackson

Here we were, almost 10 years into the new South Africa South Africa

“That is bullshit, utter bullshit. This is the new South Africa Jackson Jackson Jackson Jackson

does it cost more than the original quote?” “Because you want a white cemetery”, she replied. “This too is utter bullshit. The white cemetery costs more than the black cemetery? Does the ground cost more?” I asked as I paid. “Will the Health Department dig the grave?”, I asked. “No”, she fumed. “OK, we will do it ourselves. Thank you for all your help”, I said sarcastically as we left. Jackson Jackson

We woke up to a perfectly brilliant sunshine day: a perfect day for digging a grave. Surely not such a big job for Jackson, Amore, the kids and I? We had a pick and two spades so it would be fairly easy. It had to be done today because the funeral was tomorrow. We would cover the grave overnight with plastic, just in case it rained. Just after noon, the three of us took the plastic, pick, spades and water bottles and went to the cemetery. We found the grave site fairly easily. The Department of Health had drawn an outline of the size of the grave into the hard earth. Starting with the two spades, we dug around the marked areas. This is where we encountered our first problem. The earth was so hard that the spades bounced back up from the ground when we thrust them into the ground. We tried jumping onto the spades so that the shock of the bouncing would be less on our arms. When this seemed like a losing battle, we resorted to the pick. Amore and I had tried the spades, so now it was Jackson

An hour and a half had gone past and we had gone down 4 inches. We needed to get to five feet. The earth was hard, dry clay. We could not stop. We took it in turns with the pick and the spade and made slow progress. We stopped talking. It was too hot and we

were too tired to talk. We just wanted to get the job done. The only sounds were the sounds of the pick and the spade on the hard baked earth and our panting. There was not a breath of wind. Three hours later, we were down to three feet, but now we could not use the pick. The area of the small grave was too small to stand in and swing the pick. It was spades only and we were getting nowhere. “Let’s go and get the big boys to come and help us”, I said. “What we need here are some metal tins to use to scrape the ground out and they will be small enough to get into the grave and do it”. By now the wind had started to pick up and there were dark clouds brewing in the south, a sure sign of a summer storm. We would have to move fast.

When Matthew, Mark, William and John arrived with their mbozo’s (tins), they got into the grave and started working on clearing the ground. It was hard work for them as well. We tried to stack all the ground that we were taking out up on the one side of the grave so that it would be easier to fill in after the burial. This would also make it easier for us to get the coffin into the grave. While they were working and we were encouraging them, the rain started coming down, so I rushed over to the van and got the plastic sheet. We all huddled under the plastic sheet, the boys in the grave and the three adults sitting around it while the storm got worse and worse. The wind buffeted the plastic sheet and it took all the adult strength to keep it from flying away. As fast as the storm had arrived, it stopped. Off came the plastic sheet and back to work we went.

The cemetery is bordered by a well-used road that runs parallel with the fence and leads to the predominantly coloured area called Midros. Seeing this group of blacks and only one white woman sparked something in the people who were driving past and they started shouting obscenities at us. Some told us to get out of the white cemetery. Whites drove past and shouted “Wat maak julle daar? Kom daar uit!” (What are you doing there? Get out of there!) At three and a half feet, the rain came down in buckets again. Again we sheltered under our plastic cover, but we were wet and cold.

When the rain stopped, we would dig again. And so the afternoon continued. Digging, raining, sheltering, people shouting at us, digging, sheltering: it seemed never to stop. “Will they know if we don’t dig all the way to five feet?” asked Amore. “No, but I think we should continue”, I said, having visions of a flood and this coffin floating out of the ground. This was the first grave I was digging and I did not want to get it wrong. Looking back on this now, I wonder why I never doubted myself, what made me just go ahead as though nothing was impossible? It was dark and still we had not reached five feet. This called for torches, and so we continued to dig with tins while using torches to light our way. Eventually we finished at about nine that night. “I hope no one else dies because I am not digging any more graves”, said Matthew as we got home. I hugged him and thought, “Yes boy, I hope we never have to dig another grave”.

The next day, I went to fetch Luke from the mortuary and Amore and I dressed him in “our” favorite clothes. We wrapped him in his favorite blanket and put him in his specially designed coffin. We all left for church at the same time, with Jackson

Luke’s funeral that day was simple, beautiful and a celebration of his life. It was also a time to remember how grateful and honoured we were to have loved Luke and to have been with him for those many months. The funeral service at the Catholic Church was sad, with the children singing hymns. I sobbed when they sang “Goodbye goodbye” to Luke. I sat there remembering how Luke got one tooth at the bottom first, then one at the top. Then he got another at the bottom and then another at the top. He only ever had four front teeth. He loved his milk biscuits and Vienna

Luke’s mother died four months after Luke. There was no money to bury her. She lay in the municipal mortuary for five months before she was given a pauper’s funeral.

The smaller children still ask me when we go past the cemetery, “Mama D, can’t we wake Luke up now? He has been sleeping long enough”. They do not understand the concept of death.

The ‘white’ cemetery is no longer ‘white’. Everyone can be buried under the beautiful trees in the most beautiful cemetery in Middelburg. Many people of colour are buried there today. I doubt if they spare a thought for the little black boy who was the first to lie amongst the fancy marble headstones of the apartheid whites only area: or a thought for the woman who fought so hard for that plot: or the rag tag band who dug the grave with jam tins.

0 comments:

Post a Comment